Eurabian Dreams & Modern Nightmares

Yours Truly Reads Aloud Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas' 'Islam & Secularism'

The Eurabian Caliphate’s capital is a showcase of retro-futurism, where the grand bazaars and palaces of old are revitalized with technology that mimics natural processes. AI-guided environmental systems optimize water and energy use without compromising the aesthetic or spiritual significance of historic sites. Interactive holographic displays in public squares teach passersby about Islamic history and ecological science, inviting them to engage with their environment and heritage in new ways. This blend of nostalgia and innovation fosters a deep connection to both roots and progress, emphasizing that the path forward can indeed be illuminated by the lanterns of the past.

What follows is a Complete reading aloud of Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas’ ‘Islam & Secularism’ by Yours Truly! The full text is likewise available down below!

Professor Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas was born in Bogor, West Java. He received his early education in Sukabumi and Johor Bahru. He later studied at the Royal Military Academy, Sandhurst, England and, subsequently, at the University of Malaya, McGill University (MA) and the University of London (PhD) focusing on Islamic philosophy, theology and metaphysics.

He has written over 30 books in the fields of Islamic philosophy, theology and metaphysics, history, literature, art and civilization, religion and education. He is among the few contemporary scholars who is also thoroughly rooted in the traditional Islamic sciences. His magnum opus is Prolegomena to the Metaphysics of Islam and his latest book (2023) is Islām: The Covenants Fulfilled.

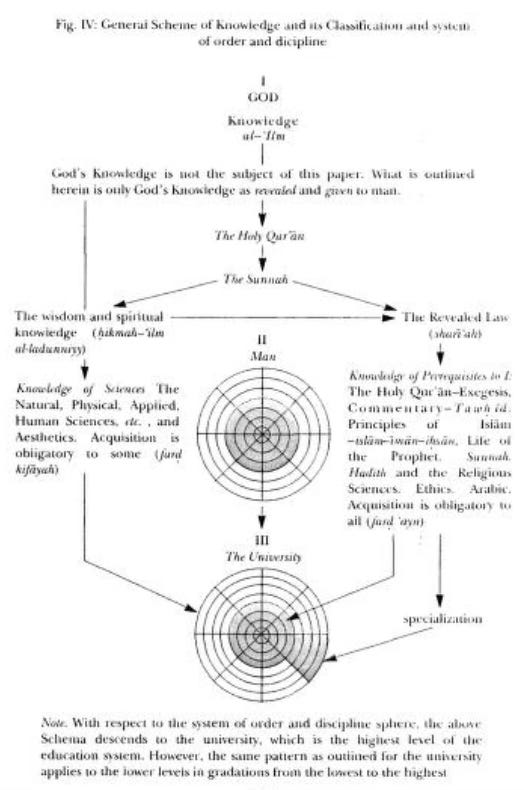

As a scholar of Islam, he has made significant contributions to the contemporary world of Islam in the domains of the Islamization of contemporary knowledge and of Muslim education. He was responsible for the conceptualization of the Islamic University, which he initially formulated at the First World Conference on Muslim Education, held in Makkah (1979). In 1987, Tan Sri Syed Naquib founded and directed the International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization (ISTAC), which is a major, global academic institution. He has inspired a generation of new scholars including Professor Wan Mohd Nor Wan Daud, who is the current holder of The Distinguished Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas Chair of Islamic Thought at the Universiti Teknologi Malaysia (UTM).

For those interested in supporting the Shaykh’s work, here is a link to his Amazon page!

Meanwhile, here is an Amazon link to purchase ‘Islam & Secularism,’ for those looking for a hardcover &/or paperback to ‘follow along with’ the Read Aloud!

While the book itself was published nearly 50 years ago, the Shaykh’s call to the Muslim Youth remains more powerful today than ever before, given the rapidly unfolding Ecological, Geopolitical, Ideological & Socioeconomic trends worldwide.

The Ummah today is over 2+ billion souls strong, with Muslims found in every continent ( including Antarctica! ) & in every area of life. Yet, Islam as that complete world system for the benefit of all mankind.. that remains elusive to scholars & activists alike.

Muslim polities (such as Qatar, the UAE, etc. ) are today fabulously wealthy. Then there are others like Pakistan, Indonesia, etc. who are key players in the world of Geopolitics, Socioeconomics, etc. Some, like Turkey, are indispensable to Global Security!

Then there are Muslim polities like Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq & others meanwhile that control the very ‘blood & guts’ of the economy. By holding the Lion’s share of Crude Oil, Natural Gas & their derivatives, these nations are essential to World Food & Energy Security.

Individual Muslims, Muslim communities & the Ummah, writ large, are thus not ‘powerless.’

Indeed, All Power Belongs Ultimately to the Lord of the Worlds, the Creator of the Heavens & The Earth, yet has He not endowed His Slaves with ample sustenance?

The Noble Qu’ran says:

وَمَا مِن دَآبَّةٍۢ فِى ٱلْأَرْضِ إِلَّا عَلَى ٱللَّهِ رِزْقُهَا وَيَعْلَمُ مُسْتَقَرَّهَا وَمُسْتَوْدَعَهَا ۚ كُلٌّۭ فِى كِتَـٰبٍۢ مُّبِينٍۢ ٦۞

There is no moving creature on earth whose provision is not guaranteed by Allah. And He knows where it lives and where it is laid to rest. All is ˹written˺ in a perfect Record.1

Muslims worldwide must reflect therefore, not on their ‘powerlessness,’ but rather the division, discord & disunity prevalent in the Ummah, due to the hesitation to fully embrace Allah Most High’s religion (in its entirety) without Apology & Pandering to Others.

Project Eurabia must likewise be without Apology & Pandering. There is no need for Islam to be ‘compatible’ with Modernity & its various ills. The Western world today stands for nothing save for War, Pornography, Usury & Materialism. There can be no concord with such a Farce.

As we shall see throughout ‘Islam & Secularism,’ The Shaykh does not in anyway shy away from stating the obvious (time & again) to all those who pay attention:

Islam & Islamization alone will be what rescues the West from the Evils of Secular Modernity.

The Noble Qu’ran says:

حُرِّمَتْ عَلَيْكُمُ ٱلْمَيْتَةُ وَٱلدَّمُ وَلَحْمُ ٱلْخِنزِيرِ وَمَآ أُهِلَّ لِغَيْرِ ٱللَّهِ بِهِۦ وَٱلْمُنْخَنِقَةُ وَٱلْمَوْقُوذَةُ وَٱلْمُتَرَدِّيَةُ وَٱلنَّطِيحَةُ وَمَآ أَكَلَ ٱلسَّبُعُ إِلَّا مَا ذَكَّيْتُمْ وَمَا ذُبِحَ عَلَى ٱلنُّصُبِ وَأَن تَسْتَقْسِمُوا۟ بِٱلْأَزْلَـٰمِ ۚ ذَٰلِكُمْ فِسْقٌ ۗ ٱلْيَوْمَ يَئِسَ ٱلَّذِينَ كَفَرُوا۟ مِن دِينِكُمْ فَلَا تَخْشَوْهُمْ وَٱخْشَوْنِ ۚ ٱلْيَوْمَ أَكْمَلْتُ لَكُمْ دِينَكُمْ وَأَتْمَمْتُ عَلَيْكُمْ نِعْمَتِى وَرَضِيتُ لَكُمُ ٱلْإِسْلَـٰمَ دِينًۭا ۚ فَمَنِ ٱضْطُرَّ فِى مَخْمَصَةٍ غَيْرَ مُتَجَانِفٍۢ لِّإِثْمٍۢ ۙ فَإِنَّ ٱللَّهَ غَفُورٌۭ رَّحِيمٌۭ ٣

Prohibited to you are dead animals,1 blood, the flesh of swine, and that which has been dedicated to other than Allāh, and [those animals] killed by strangling or by a violent blow or by a head-long fall or by the goring of horns, and those from which a wild animal has eaten, except what you [are able to] slaughter [before its death], and those which are sacrificed on stone altars,2 and [prohibited is] that you seek decision through divining arrows. That is grave disobedience. This day those who disbelieve have despaired of [defeating] your religion; so fear them not, but fear Me. This day I have perfected for you your religion and completed My favor upon you and have approved for you Islām as religion. But whoever is forced by severe hunger with no inclination to sin - then indeed, Allāh is Forgiving and Merciful.

Without blemish or fault, Islam, therefore, stands alone as that Complete System for All Mankind, that system which will bring European man back from the Abyss of Modernity. Eurabia’s Ascension is not to be feared, therefore, but celebrated!

The Old World is Dead.

It will not be coming back, nor should it be missed. What Eurabians should look forward to is Revival & Restoration, of that once Optimistic pro-human spirit & soul that was snuffed out by the worship of ‘Progress,’ Technology, Space travel & related ills.

Likewise, the time has come to eschew Nationalism.

The Ummah & its polities must take a Giant Sledgehammer to the cancerous ideology of Nationalism, that divisive force which runs on fear, anger & victimization for its sustenance… motivators which the Believer, Ipso Facto, must reject.

The Time has come for Medina & Athena to restore its once illustrious marriage, that marriage between Faith & Reason which was not just the envy of whole nations, peoples & Civilizations, but likewise the entire world.

Western man’s Faustian, Nietzschean, Vitalist Soul has reached ( & passed ) its zenith.

The German polymath Oswald Spengler noted nearly a century ago:

And then, when being is sufficiently uprooted and waking-being sufficiently strained, there suddenly emerges into the bright light of history a phenomenon that has long been preparing itself underground and now steps forward to make an end of the drama—the sterility of civilized man. This is not something that can be grasped as a plain matter of causality (as modern science naturally enough has tried to grasp it); it is to be understood as an essentially metaphysical turn towards death. The last man of the world-city no longer wants to live—he may cling to life as an individual, but as a type, as an aggregate, no, for it is a characteristic of this collective existence that it eliminates the terror of death. That which strikes the true peasant with a deep and inexplicable fear, the notion that the family and the name may be extinguished, has now lost its meaning. The continuance of the blood-relation in the visible world is no longer a duty of the blood, and the destiny of being the last of the line is no longer felt as a doom. Children do not happen, not because children have become impossible, but principally because intelligence at the peak of intensity can no longer find any reason for their existence.

~ The Decline of the West; Vol. II, Alfred A. Knopf, 1928, pp. 103–04

The New World is being born as we speak. It is a world in which the Faustian soul of Western man, long ago rendered sterile & inert, is being assimilated by the Magian soul of Ishmael to breathe back to life once more, a rapidly emptying continent.

In this New World, the Eurabian Peninsula will, Inshallah, once more thrive!

I pray that You, Dear Readers & Listeners, may find ample benefit in my Dictation!

Whatever I have said that was in error is from myself, & whatever that was said was True is from Allah Most High.

& with that, Yours Truly shall begin Reading Aloud the Shaykh’s Excellent Book! 😉

Islām & Secularism

By Syed Muhammad Naquib Al-Attas

First Impression 1978, Second Impression 1993

The daily life in a Eurabian metropolis showcases the practical blend of Islām and secularism. The cityscape is dotted with minarets and secular monuments, and public broadcasts feature calls to prayer alongside news updates. In the bustling marketplaces, vendors sell halal food next to secular bookshops and art galleries. This scene demonstrates the seamless integration of religious observance and secular freedom, where citizens navigate their identities and values in a diverse, inclusive society.

TO THE MUSLIM YOUTH

Contents

Author’s Note to the First Edition

Preface to the Second Printing

I. The Contemporary Western Christian Background

II. Secular-Secularization-Secularism

III. Islām: The Concept of Religion and the Foundation of Ethics and Morality

V. The Dewesternization of Knowledge

→ Definition and Aims of Education

→ Islamic System of Order and Discipline

→ Concluding Remarks and Suggestions

Appendix— On Islamization: The Case of the Malay-Indonesian Archipelago

Author’s Note To The First Edition

In the heart of the Eurabian Caliphate, sprawling urban gardens rise alongside retrofitted historical buildings, blending timeless Islamic architecture with cutting-edge ecological technologies. Solar panels and wind turbines integrate seamlessly into the ornate designs of mosques and public buildings, reflecting a commitment to sustainability. The streets bustle with electric vehicles and bicycles, and public spaces are alive with community farming and renewable energy workshops. This ecotechnic retrotopia combines the wisdom of the past with the innovations of the future, creating a sustainable model for urban living that respects both cultural heritage and environmental needs.

The present book is a development of ideas contained in the many paragraphs of another book in Malay entitled: Risalah Untuk Kaum Muslimin, which I wrote and completed during the first few months of 1974. Due to many circumstances which demanded my attention at home and abroad, however, the Risalah has not yet been sent to the press.

In this book, what is contained in Chapter III was composed and completed during the month of Ramaḍān of 1395 (1975), and delivered as a Lecture under the same title to the International Islamic Conference held in April 1976 at the Royal Commonwealth Society, London, in conjunction with the World of Islam Festival celebrated there that year. It was published as a monograph in the same year by the Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia (ABIM), Kuala Lumpur, and in 1978 it appeared, together with other Lectures delivered on the same occasion by various Muslim scholars, in a book of one volume entitled: The Challenge of Islam, edited by Ataf Gauhar and published by the Islamic Council of Europe, London.

All the other Chapters of the book were begun in March 1977 and completed in April of the same year, during my appointment as Visiting Scholar and Professor of Islamics at the Department of Religion, Temple University, Philadelphia, U.S.A., in the Winter and Spring of 1976-1977. What is contained in Chapter V was presented as a Paper entitled: Preliminary Thoughts on the Nature of Knowledge and the Definition and Aims of Education, addressed to the First World Conference on Muslim Education held at Mecca in April 1977. It will appear, together with other selected Papers of the Conference, in a book entitled: Aims and Objectives of Islamic Education, edited with an introduction by myself and published by King Abdulaziz University and Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1979, as one of a series of seven books.

Kuala Lumpur, Muḥarram 1399/December 1978.

Preface To The Second Printing

Picture a panorama of the Eurabian Caliphate where every city skyline is a mosaic of green rooftops, vertical forests, and traditional minarets. Each building is a self-sustaining ecosystem, with rainwater harvesting systems and walls that breathe life through bio-adaptive botanical technologies. Markets thrive on locally sourced goods and artisan crafts that employ age-old techniques powered by renewable energy. The society is a beacon of environmental stewardship and cultural preservation, showcasing how advanced technologies and ancient traditions can coexist in a symbiotic and sustainable relationship.

Almost twenty years have elapsed since the first printing of this book, but the seminal ideas pertaining to the problem of Muslim education and allied topics of an intellectual and revolutionary nature, such as the idea of Islamization of contemporary knowledge and a general definition of its nature and method, and the idea of the Islamic University, the conceptualization of its nature and final establishment, were formulated much earlier in the mid-nineteen-sixties. They were formulated, elaborated, and disseminated here in Malaysia and abroad in academic lectures and various conferences and more than 400 public lectures, and were born out of the need for creative thinking and clarification of the basic concepts based upon the religious and intellectual tradition of Islam, and upon personal observation and reflection and conceptual analysis throughout my teaching experience in Malaysian universities since 1964. These ideas have also been communicated to the Islamic Secretariat in Jeddah in early 1973, at the same time urging the relevant authorities to convene a gathering of reputable scholars of Islam to discuss and deliberate upon them.1 There is no doubt that these ideas have been instrumental in the convening of the First World Conference on Muslim Education held at Mekkah in early 1977, where the substance of Chapter V of this book was published in English and Arabic and read as a keynote address at the Plenary Session.2 In 1980, a commentary of a few paragraphs of that Chapter pertaining to the concept of education in Islām was presented and read as a keynote address at the Plenary Session of the Second World Conference on Muslim Education held at Islamabad early the same year.3

Thenceforth, for the successive convenings of the World Conference on Muslim Education held in various Muslim capital cities, I was not invited and my ideas have been appropriated without due acknowledgment and propagated since 1982 by ambitious scholars, activists, academic operators and journalists in vulgarized forms to the present day.4 Muslims must be warned that plagiarists and pretenders as well as ignorant imitators affect great mischief by debasing values, imposing upon the ignorant, and encouraging the rise of mediocrity. They appropriate original ideas for hasty implementation and make false claims for themselves. Original ideas cannot be implemented when vulgarized; on the contrary, what is praiseworthy in them will turn out to become blameworthy, and their rejection will follow with the dissatisfaction that will emerge. So in this way authentic and creative intellectual effort will continually be sabotaged. It is not surprising that the situation arising out of the loss of adab also provides the breeding ground for the emergence of extremists who make ignorance their capital.

Since the value and validity of new ideas can best be developed and clarified along logical lines by their original source, I have by means of my own thought, initiative and creative effort, and with God’s succour and the aid of those whom God has guided to render their support, conceived and established an international Institute aligned to the purpose of the further development, clarification and correct implementation of these ideas until they may come to full realization.

The International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization (ISTAC), although formulated and conceptualized much earlier, was officially opened in 1991, and among its most important aims and objectives are to conceptualize, clarify, elaborate, scientific and epistemological problems encountered by Muslims in the present age; to provide an Islamic response to the intellectual and cultural challenges of the modern world and various schools of thought, religion, and ideology; to formulate an Islamic philosophy of education, including the definition, aims and objectives of Islamic education; to formulate an Islamic philosophy of science; to study the meaning and philosophy of Islamic art and architecture, and to provide guidance for the Islamization of the arts and art education; to publish the results of our researches and studies from time to time for dissemination in the Muslim World; to establish a superior library reflecting the religious and intellectual traditions both of the Islamic and Western civilizations as a means to attaining the realization of the above aims and objectives. Those with understanding and discernment will know, when they ponder over the significance of these aims and objectives, that these are not merely empty slogans, for they will realize that these aims and objectives reflect a profound grasp of the real problems confronting the contemporary Muslim world. The aims and objectives of the Institute are by no means easy to accomplish. But with concerted effort from dedicated and proven scholars who will deliberate as a sort of organic body which is itself rooted in authentic Islamic learning and are at the same time able to teach various modern disciplines, we shall, God willing, realize the fulfillment of our vision. Even so, a significant measure of these aims and objectives has in fact already been realized in various stages of fulfillment. Concise books have already been published by ISTAC outlining frameworks for Islamic philosophies of education including its definition and its aims and objectives;5 of science;6 of psychology and epistemology;7 as well as other such works which altogether will be integrated to project what I believe to be the worldview of Islām.8 It is within the framework of this worldview, formulated in terms of a metaphysics, that our philosophy of science and our sciences in general must find correspondence and coherence with truth. ISTAC has already begun operating as a graduate institution of higher learning open to international scholars and students engaged in research and studies on Islamic theology, philosophy, and metaphysics; science, civilization, languages and comparative thought and religion. It has already assembled a respectable and noble library reflecting the fields encompassing its aims and objectives; and the architecture of ISTAC is itself a concrete manifestation of artistic expression that springs from the well of creative knowledge.9

This book was originally dedicated to the emergent Muslims, for whose hearing and understanding it was indeed meant, in the hope that they would be intelligently prepared, when their time comes, to weather with discernment the pestilential winds of secularization and with courage to create necessary changes in the realm of our thinking that is still floundering in the sea of bewilderment and self-doubt. The secularizing ‘values’ and events that have been predicted would happen in the Muslim world have now begun to unfold with increasing momentum and persistence due still to the Muslims’ lack of understanding of the true nature and implications of secularization as a philosophical program. It must be emphasized that our assault on secularism is not so much directed toward what is generally understood as ‘secular’ Muslim state and government, but more toward secularization as a philosophical program, which ‘secular’ Muslim states and governments need not necessarily have to adopt. The common understanding among Muslims, no doubt indoctrinated by Western notions, is that a secular state is a state that is not governed by the ulamā’, or whose legal system is not established upon the revealed law. In other words, it is not a theocratic state. But this setting in contrast the secular state with the theocratic state is not really an Islamic way of understanding the matter, for since Islām does not involve itself in the dichotomy between the sacred and the profane, how then can it set in contrast the theocratic state with the secular state? An Islamic state is neither wholly theocratic nor wholly secular. A Muslim state calling itself secular does not necessarily have to oppose religious truth and religious education; does not necessarily have to divest nature of spiritual meaning; does not necessarily have to deny religious values and virtues in politics and human affairs. But the philosophical and scientific process which I call ‘secularization’ necessarily involves the divesting of spiritual meaning from the world of nature; the desacralization of politics from human affairs; and the deconsecration of values from the human mind and conduct. Remember that we are a people neither accustomed nor permitted to lose hope and confidence, so that it is not possible for us simply to do nothing but wrangle among ourselves and rave about empty slogans and negative activism while letting the real challenge of the age engulf us without positive resistance. The real challenge is intellectual in nature, and the positive resistance must be mounted from the fortification not merely of political power, but of power that is founded upon right knowledge.

We are now again at the crossroads of history, and awareness of Islamic identity is beginning to dawn in the consciousness of emergent Muslims. Only when this awareness comes to full awakening with the sun of knowledge will there emerge from among us men and women of spiritual and intellectual maturity and integrity who will be able to play their role with wisdom and justice in upholding the truth. Such men and women will know that they must return to the early masters of the religious and intellectual tradition of Islām, which was established upon the sacred foundation of the Holy Qur’ān and the Tradition of the Holy Prophet, in order to learn from the past and be able to acquire spiritually and intellectually for the future; they will realize that they must not simply appropriate and imitate what modern Western civilization has created, but must regain by exerting their own creative knowledge, will, and imagination what is lost of the Muslims’ purpose in life, their history, their values and virtues embodied in their sciences, for what is lost can never be regained by blind imitation and the raving of slogans which deafen with the din of ‘development’; they will discern that development must not involve a correspondence of Islām with the facts of contemporary events that have strayed far from the path of truth;10 and they will conceive and formulate their own definitions and conceptions of government and of the nature of development that will correspond with the purpose of Islām. Their emergence is conditional not merely upon physical struggle, but more upon the achievement of true knowledge, confidence and boldness of vision that is able to create great changes in history.

Kuala Lumpur, 27 Muḥarram 1414 / 17 July 1993

بسم الله الرحمن الرحيم

الحمد لله رب العالمين

الصلاة والسلام على أشرف الأنبياء والمرسلين

I. The Contemporary Western Christian Background

Empty Pews and Silent Bells: Depict a once-bustling church in a Western city, now facing a decline with empty pews and unused hymn books gathering dust. The stained glass still casts colorful light across the vacant interior, but there is a palpable silence where there once was the sound of communal singing and prayer. Outside, the church’s architecture stands stark against a modern skyline, overshadowed by bustling commercial buildings and digital billboards, illustrating the shift from spiritual to secular life in contemporary society.

About ten years ago11 the influential Christian philosopher and one regarded by Christians as among the foremost of this century, Jacques Maritain, described how Christianity and the Western world were going through a grave crisis brought about by contemporary events arising out of the experience and understanding and interpretation of life in the urban civilization as manifested in the trend of neo-modernist thought which emerged from among the Christians themselves andF the intellectuals — philosophers, theologians, poets, novelists, writers, artists — who represent Western culture and civilization.12 Since the European Enlightenment, stretching from the 17th to the 19th centuries, and with the concomitant rise of reason and empiricism and scientific and technological advances in the West, English, Dutch, French and German philosophers have indeed foreshadowed in their writings the crisis that Maritain described, though not quite in the same manner and dimension, for the latter was describing in conscious and penetrating perception the events of contemporary experience only known as an adumbrated prediction in the past. Some Christian theologians in the earlier half of this century also foresaw the coming of such a crisis, which is called secularization. Already in the earlier half of the 19th century the French philosopher-sociologist, Auguste Comte, envisaged the rise of science and the overthrow of religion, and believed, according to the secular logic in the development of Western philosophy and science, that society was ‘evolving’ and ‘developing’ from the primitive to the modern stages, and observed that taken in its developmental aspect metaphysics is a transition from theology to science;13 and later that century the German philosopher-poet and visionary, Friedrich Nietzsche, prophesied through the mouth of Zarathustra— at least for the Western world — that God is dead.14 Western philosophers, poets, novelists have anticipated its coming and hailed it as preparing for an ‘emancipated’ world with no ‘God’ and no ‘religion’ at all. The French Jesuit, pale-ontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, followed by other theologians like the German Dietrich Bonhoeffer and the American Paul Tillich, sensing the trend of contemporary events and the thoughts that recognized their significance to Christianity and the Western world, began to accept the inevitability of the impending religious and theological crisis that would emerge as a result of secularization, and being already influenced by it they counseled alignment and participation in the process of secularization, which is seen by many as irresistibly spreading rapidly throughout the world like a raging contagion.15 The Nietzschean cry that ‘God is dead’, which is still ringing in the Western world, is now mingled with the dirge that ‘Christianity is dead’, and some of the influential theologians among the Christians — particularly the Protestants, who seem to accept the fate of traditional Christianity as such, and are more readily inclined toward changing with the times — have even started to initiate preparations for the laying out of a new theological ground above the wreckage in which lay the dissolute body of traditional Christianity, out of which a new secularized Christianity might be resurrected. These theologians and theorists align themselves with the forces of neo-modernist thought. They went so far as to assert triumphantly, in their desire to keep in line with contemporary events in the West, that secularization has its roots in biblical faith and is the fruit of the Gospel and, therefore, rather than oppose the secularizing process, Christianity must realistically welcome it as a process congenial to its true nature and purpose. European and American theologians and theorists like Karl Barth, Friedrich Gogarten, Rudolph Bultmann, Gerhard von Rad, Arend van Leeuwen, Paul van Buren, Harvey Cox and Leslie Dewart — and many more in Europe, England and America, both Catholic and Protestant — have found cause to call for radical changes in the interpretation of the Gospel and in the nature and role of the Church that would merge them logically and naturally into the picture of contemporary Western man and his world as envisaged in the secular panorama of life.16 While some of the Christian theologians and intellectuals think that the religious and theological crisis felt by them has not yet taken hold of the Christian community, others feel that the generality among them and not only the intellectuals are already enmeshed in the crisis. Its grave implications for the future of traditional Christianity is widely admitted, and many are beginning to believe in the predictions of the Austrian psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud, whose The Future of an Illusion17 is regarded as the greatest assault on theism in Western history. Furthermore the Christians who on the whole are apparently opposed to secularization, are themselves unconsciously assiduous accomplices in that very process, to the extent that those aware of the dilemma confronting them have raised general alarm in that there has now emerged with increasing numbers and persistence what Maritain has called “immanent apostasy” within the Christian community.18 Indeed many Christian theologians and intellectuals forming the avant-garde of the Church are in fact deeply involved in ‘immanent apostasy’, for while firmly resolving to remain Christian at all costs they openly profess and advocate a secularized version of it, thus ushering into the Christian fold a new emergent Christianity alien to the traditional version to gradually change and supplant it from within. In such a state of affairs it is indeed not quite an exaggeration to say that we are perhaps spectators of events which may yet lead to another Reformation in Christian history.19 The theologians and intellectuals referred to above are not only preparing ground for a new secularized version of Christianity, but they also tragically know and accept as a matter of historical fact that the very ground itself will be ever-shifting, for they have come to realize, by the very relativistic nature of their new interpretation, that that new version itself — like all new versions to come — will ultimately again be replaced by another and another and so on, each giving way to the other as future social changes demand. They visualize the contemporary experience of secularization as part of the ‘evolutionary’ process of human history; as part of the irreversible process of ‘coming of age’, of ‘growing up’ to ‘maturity’ when they will have to ‘put away childish things’ and learn to have ‘the courage to be’; as part of the inevitable process of social and political change and the corresponding change in values almost in line with the Marxian vision of human history. And so in their belief in permanent ‘revolution’ and permanent ‘conversion’ they echo within their existential experience and consciousness the confession of the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard: “We are always becoming Christians.”20 Thus they naturally advocate in their attempt to align themselves with secularization a reconceptualization of the Christian Gospel; a redefinition of their concept of God; a dehellenization of Christian dogma. And Christianity, by virtue of its cultural nature and developmental experience, and based as it has always been upon a historically shifting foundation of hermeneutics, might lend itself easily to the possible realization of their vision of the future. This trend of events, disconcerting to many traditional Christians, is causing much anxiety and foreboding and reflected plainly in Mascall’s book where he reiterates that instead of converting the world to Christianity they are converting Christianity to the world.21 While these portents of drastic change have aroused the consternation of the traditional Catholic theologians, whose appeals of distress have caused Pope John XXIII to call for an aggiornamento to study ways and means to overcome, or at least to contain, the revolutionary crisis in the Christian religion and theology, and to resist secularization through the enunciation of the ecumenical movement, and the initiation of meaningful dialogues with Muslims and others, in the hope not only of uniting the Christian community but of enlisting our conscious or unconscious support as well in exorcising the immanent enemy, they nonetheless admit, albeit grudgingly, that their theology as understood and interpreted during these last seven centuries is now indeed completely out of touch with the ‘spirit of the times’ and is in need of serious scrutiny as a prelude towards revision. The Protestants, initiated by the 19th century German theologian and historian of the development of Christian dogma, Adolf von Harnack, have since been pressing for the dehellenization of Christianity;22 and today even Catholics are responding to this call, for now they all see that, according to them, it was the casting of Christianity in Hellenic forms in the early centuries of its development that is responsible, among other tenacious and perplexing problems, for the conceiving of God as a suprarational Person; for making possible the inextricably complicated doctrine of the Trinity; for creating the condition for the possibility of modern atheism in their midst — a possibility that has in fact been realized. This is a sore point for the Catholic theologians who cleave to the permanence of tradition, who realize that the discrediting of Hellenic epistemology — particularly with reference to the Parmenidean theory of truth, which formed the basis of Scholastic thought centered on the Thomistic metaphysics of Being — must necessarily involve Catholicism in a revolution of Christian theology. For this reason perhaps — that is, to meet the challenge of the Protestant onslaught which came with the tide of the inexorable advance of Modernist thought in the European Enlightenment, and the logical development of the epistemological theory and method of the French philosopher, René Descartes, which greatly influenced the form in which European philosophy and science was to take — renewed interest in the study of Thomistic metaphysics have gained momentum this century among Catholic philosophers such as Maritain, Etienne Gilson and Joseph Maréchal, who each has his own school of interpretation cast within the infallible metaphysical mould fashioned by the Angelic Doctor. But some of the disciples of the former two, notably Dewart23 and his followers, while not going as far as Von Harnack in condemning hellenization as the perpetrator in the corruption of Christian dogma, nonetheless admit that hellenization has been responsible for retarding the development of Christian dogma, restricting its growth, as it were, to the playpen of philosophical enquiry and its development to the kindergarten of human thought. So in ‘a world come of age’, they argue controversially, Christian thought must no longer — cannot any longer — be confined to the crib of childish and infantile illusions if it were to be allowed to rise to the real challenge of maturity. And thus with new impetus derived from the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl and the existentialism of Martin Heidegger, and further fortified by recent advances in linguistic analyses contributed by the philosophers of language, notably those belonging to the Vienna Circle,24 they press on vigorously for the demythologization of Christian scripture and the dehellenization of its dogma.

Whatever the outcome may be Christians as a whole do not deny that their most serious problem is the ‘problem of God’. Already as alluded to briefly in connection with the Parmenidean correspondence theory of truth, the problem of God is outlined against the background of the problem of the existence of objects. Since according to Parmenides thought and being are identical, and being is that which fills space, it follows that in the correspondence theory of truth a proposition or an uttered thought or meaning is true only if there is a fact to which it corresponds, being as such is necessary. The later Greek philosophers including Plato and Aristotle never doubted the necessity of being. Indeed, to regard being as necessary was the essential element of the Greek world view. However they distinguished between the necessity of being as such — that is, as concrete reality, existing as actuality as a whole — and individual beings, regarding individual beings as contingent. The being of the world as such is necessary and hence also eternal, but individual beings, including that of a man, are contingent as they have an origination in time and space and suffer change and dissolution and final end. The being of man as a species, however, like the being of the world as such, is necessary and indeed also eternal. It is quite obvious that when Christianity officially adopted Aristotelian philosophy into its theology,25 it had to deny necessary being to the creatures and affirm necessary being only to God who alone is Eternal. Thus whereas Christian scholastic theology, like the Greeks, affirmed God as the Supreme Being Whose Being is Necessary, it did not regard the being of the world and nature as necessary, for as created being the world is by nature contingent. However, since it continued to adopt the Parmenidean epistemology, and while it denied necessary being to the creatures, it could not deny the necessity of the being of creatures as to their intelligibility; hence the creatures are contingent as to their being, but necessary as to their being in thought. In this way the identity of being — and also its necessity — and intelligibility is retained. Since a distinction was made between necessary being and contingent being, and with reference to the creatures their being necessary is in thought and not in actuality, a real distinction was thus made between essence and existence in creatures. The essence of the creature is its being in thought, and this is necessary; its existence is its actuality outside of thought, and this is contingent. As to God, it was affirmed that obviously His Essence should be identical with His Existence as Necessary Being. This distinction between essence and existence in creatures was apparently made on the basis of Thomas Aquinas’ observation, which in turn seems to have been based on a misunderstanding of Avicenna’s position, that every essence or quiddity can be understood without anything being known of its existing, and that, therefore, the act of existing is other than essence or quiddity.26 The only Being whose quiddity is also its very act of existing must be God. It was this observation that made William of Ockham, less than a hundred years later, to draw the far reaching conclusion that if every essence or quiddity can be understood without anything being known of its existing, then no amount of knowledge could possibly tell us whether it actually existed. The conclusion drawn from this was that one would never be able to know that anything actually exists. From the ensuing doubt that Ockham raised about the existence of objects, it follows that the existence of God is likewise cast in doubt. Our knowledge of things is based upon the existence of objects. Even if the external existence of objects remain problematic, at least their being in thought is known. But their being in thought, which constitute ‘formal’ knowledge, can also possibly be caused, as such, by an efficient cause other than the actually existing objects — such as by God, or by the very nature of the mind itself — and hence, the problem as to the ‘objective’ reality of ideas becomes more complicated for philosophy and cannot be established by it. Ultimately this trend of philosophy naturally led to consequences resulting in the casting of doubt also on knowledge of the essence of the creatures, and not merely its existence. The epistemological consequences of doubting the existence and essence of objects created the ‘problem of God’. After Ockham, Descartes, following the logical course of deduction from the observation of Aquinas, sought to establish the existence of the self by his famous cogito argument, from which he ultimately based his a priori certainty for the existence of God. But his failure to prove the existence of God led to the problem becoming more acute. Descartes established the existence of the self, the existence of the individual creature, man, to himself by means of empirical intuition; this does not necessarily establish the existence of objects outside of thought. In the case of the existence of God, the more impossibly complicated it became, seeing that unlike man He is not subject to empirical intuition. Now what is more problematic about the existence of God is that since His being in thought, His Essence, cannot be known, and since His Being is identical with His Existence, it follows that His Existence also cannot be known. His Existence — in the correspondence theory of truth — can be known only if the identity of His Being and His Existence can be demonstrated rationally, which is not possible to accomplish. At least up till the present time the idea that God’s Existence can rationally be demonstrated is only a matter of faith. Philosophically, and according to the development of thought flowing from Christian Aristotelianism, which some would prefer to refer to more properly as Aristotelian Christianity, the unknowability of God, of His Existence, and of other metaphysical notions about reality and truth was finally established in the West in the 18th century by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant.27

To augment this problem of self-evolved doubt about God, the God they have conceived since the earliest periods in the development of Christian dogma was formulated on the basis of a highly improbable conceptual amalgam consisting of the theos of Greek philosophy, the yahweh of the Hebrews, the deus of Western metaphysics, and a host of other traditional gods of the pre-Christian Germanic traditions. What is now happening is that these separate and indeed mutually conflicting concepts, artificially fused together into an ambiguous whole, are each coming apart, thus creating the heightening crisis in their belief in a God which has already been confused from the very beginning. Furthermore they understand Christianity as historical, and since the doctrine of the Trinity is an integral part of it, their difficulty is further augmented by the necessity that whatever be the formulation of any new Christian theism that might possibly emerge, it must be cast in the Trinitarian crucible. The notion of person in the Augustinian concept of the Trinity is left vague, and although Boethius and Aquinas and others through the centuries till the present time have attempted to define it, the problem, like the Gordian Knot, has naturally become more complicated and elusive. In spite of their concession that very real limitations inhere in Hellenism and that modern Western culture has transcended Scholasticism, they argue that, rather than succumb to the philosophical reduction of God to a mere concept, or to a vague and nebulous presence, the vagueness of their early predecessors must be interpreted as indicating the direction in which ‘development’ is to be pursued. In this way the Hellenic thought structure is conveniently made to appear as ‘open ended’ and not ‘closed’ or impending ‘development’, so that it might readily be adapted to the equally ‘open ended’ Christian theism that may be envisaged from time to time as human ‘evolution’ in line with historical ‘development’ demands. Thus as long as God is conceived of as Three of Something it would always allow for future change with the changing world in a relativistic fashion; and this relativism allows the believer to be free to conceive whatever notion of God fancies him most, that is the scriptural, or the patristic (hellenic), or the mediaeval (scholastic), or the modern (existential) in such wise that it also allows him or her to align with ‘contemporary experience’, which is historically minded. Aside from this and because of the problematic nature of their concept of God, the very name ‘God’ itself is now becoming problematic for them, to such an extant that they even contemplate discarding it altogether and leaving it to history to coin a new name for connoting a more relevant and adequate concept to refer to the ultimate presence and reality in which they believe.

II. Secular–Secularization–Secularism

Cultural Disintegration in a Fully Secular Society: A poignant montage of once-sacred buildings and culturally significant sites that have been repurposed into commercial centers, like cafes, boutiques, and tech hubs, in a fully secular society. The visual narrative shows iconic religious architectures stripped of their spiritual symbols and repainted with vibrant, secular commercial ads, reflecting the commodification of cultural heritage. The streets are busy with consumers, indifferent to the historical and spiritual significance of the spaces they occupy. This scene underscores the loss of spiritual identity and historical continuity, presenting a society where commercial interests have supplanted cultural and religious significance, leading to a sense of historical amnesia and cultural void.

In the preceding pages I have tried to convey in brief outline and cursory sketch the real contemporary situation in the Western Christian world. Although the sketch is very brief I believe that it has at least captured in summary and true perspective the essential components comprising the fundamental problems that beset Western Christian society. We must see, in view of the fact that secularization is not merely confined to the Western world, that their experience of it and their attitude towards it is most instructive for Muslims. Islam is not similar to Christianity in this respect that secularization, in the way in which it is also happening in the Muslim world, has not and will not necessarily affect our beliefs in the same way it does the beliefs of Western man. For that matter Islam is not the same as Christianity, whether as a religion or as a civilization. But problems arising out of secularization, though not the same as those confronting the West, have certainly caused much confusion in our midst. It is most significant to us that these problems are caused due to the introduction of Western ways of thinking and judging and believing emulated by some Muslim scholars and intellectuals who have been unduly influenced by the West and overawed by its scientific and technological achievements, who by virtue of the fact that they can be thus influenced betray their lack of true understanding and full grasp of both the Islamic as well as the Western world views and essential beliefs and modes of thought that project them; who have, because of their influential positions in Muslim society, become conscious or unconscious disseminators of unnecessary confusion and ignorance. The situation in our midst can indeed be seen as critical when we consider the fact that the Muslim Community is generally unaware of what the secularizing process implies. It is therefore essential that we obtain a clear understanding of it from those who know and are conscious of it, who believe and welcome it, who teach and advocate it to the world.

The term secular, from the Latin saeculum, conveys a meaning with a marked dual connotation of time and location; the time referring to the ‘now’ or ‘present’ sense of it, and the location to the ‘world’ or ‘worldly’ sense of it. Thus saeculum means ‘this age’ or ‘the present time’, and this age or the present time refers to events in this world, and it also then means ‘contemporary events’. The emphasis of meaning is set on a particular time or period in the world viewed as a historical process. The concept secular refers to the condition of the world at this particular time or period or age. Already here we discern the germ of meaning that easily develops itself naturally and logically into the existential context of an ever-changing world in which there occurs the notion of relativity of human values. This spatio-temporal connotation conveyed in the concept secular is derived historically out of the experience and consciousness born of the fusion of the Graeco-Roman and Judaic traditions in Western Christianity. It is this ‘fusion’ of the mutually conflicting elements of the Hellenic and Hebrew world views which have deliberately been incorporated into Christianity that modern Christian theologians and intellectuals recognize as problematic, in that the former views existence as basically spatial and the latter as basically temporal in such wise that this arising confusion of worldviews becomes the root of their epistemological and hence also theological problems. Since the world has come in modern times been more and more understood and recognized by them as historical, the emphasis on the temporal aspect of it has become more meaningful and has conveyed a special significance to them. For this reason they exert themselves in efforts emphasizing their conception of the Hebrew vision of existence, which they think is more congenial with the ‘spirit of the times’, and denouncing the Hellenic as a grave and basic mistake, as can be glimpsed from the brief sketch in the preceding chapter.

Secularization is defined as the deliverance of man “first from religious and then from metaphysical control over his reason and his language”:28 It is “the loosing of the world from religious and quasi-religious understandings of itself, the dispelling of all closed world views, the breaking of all supernatural myths and sacred symbols… the ‘defatalization of history’, the discovery by man that he has been left with the world on his hands, that he can no longer blame fortune or the furies for what he does with it…; [it is] man turning his attention away from the worlds beyond and toward this world and this time.”29 Secularization encompasses not only the political and social aspects of life, but also inevitably the cultural, for it denotes “the disappearance of religious determination of the symbols of cultural integration”.30 It implies “a historical process, almost certainly irreversible, in which society and culture are delivered from tutelage to religious control and closed metaphysical world views”.31 It is a “liberating development”, and the end product of secularization is historical relativism.32 Hence according to them history is a process of secularization.33 The integral components in the dimensions of secularization are the disenchantment of nature, the desacralization of politics, and the deconsecration of values.34 By the ‘disenchantment’ of nature — a term and concept borrowed from the German sociologist Max Weber35 — they mean as he means, the freeing of nature from its religious overtones; and this involves the dispelling of animistic spirits and gods and magic from the natural world, separating it from God and distinguishing man from it, so that man may no longer regard nature as a divine entity, which thus allows him to act freely upon nature, to make use of it according to his needs and plans, and hence create historical change and ‘development’. By the ‘desacralization’ of politics they mean the abolition of sacral legitimation of political power and authority, which is the prerequisite of political change and hence also social change allowing for the emergence of the historical process. By the ‘deconsecration’ of values they mean the rendering transient and relative all cultural creations and every value system which for them includes religion and worldviews having ultimate and final significance, so that in this way history, the future, is open to change, and man is free to create the change and immerse himself in the ‘evolutionary’ process. This attitude towards values demands an awareness on the part of secular man of the relativity of his own views and beliefs; he must live with the realization that the rules and ethical codes of conduct which guide his own life will change with the times and generations. This attitude demands what they call ‘maturity’, and hence secularization is also a process of ‘evolution’ of the consciousness of man from the ‘infantile’ to the ‘mature’ states, and is defined as “the removal of juvenile dependence from every level of society… the process of maturing and assuming responsibility… the removal of religious and metaphysical supports and putting man on his own”.36 They say that this change of values is also the recurrent phenomenon of “conversion” which occurs “at the intersection of the action of history on man and the action of man on history”, which they call “responsibility, the acceptance of adult accountability”.37 Now we must take due notice of the fact that they make a distinction between secularization and secularism, saying that whereas the former implies a continuing and open-ended process in which values and worldviews are continually revised in accordance with ‘evolutionary’ change in history, the latter, like religion, projects a closed worldview and an absolute set of values in line with an ultimate historical purpose having a final significance for man. Secularism according to them denotes an ideology.38 Whereas the ideology that is secularism, like the process that is secularization, also disenchants nature and desacralizes politics, it never quite deconsecrates values since it sets up its own system of values intending it to be regarded as absolute and final, unlike secularization which relativizes all values and produces the openness and freedom necessary for human action and for history. For this reason they regard secularism as a menace to secularization, and urge that it must be vigilantly watched and checked and prevented from becoming the ideology of the state. Secularization, they think, describes the inner workings of man’s ‘evolution’. The context in which secularization occurs is the urban civilization. The structure of common life, they believe, has ‘evolved’ from the primitive to the tribal to the village to the town to the city by stages — from the simple social groupings to the complex mass society; and in the state of human life, or the stage of man’s ‘evolution’, this corresponds to the ‘development’ of man from the ‘infantile’ to the ‘mature’ state. The urban civilization is the context in which the state of man’s ‘maturing’ is taking place; the context in which secularization takes place, patterning the form of the civilization as well as being patterned by it.

The definition of secularization which describes its true nature to our understanding corresponds exactly with what is going on in the spiritual and intellectual and rational and physical and material life of Western man and his culture and civilization; and it is true only when applied to describe the nature and existential condition of Western culture and civilization. The claim that secularization has its roots in biblical faith and that it is the fruit of the Gospel has no substance in historical fact. Secularization has its roots not in biblical faith, but in the interpretation of biblical faith by Western man; it is not the fruit of the Gospel, but is the fruit of the long history of philosophical and metaphysical conflict in the religious and purely rationalistic worldview of Western man. The interdependence of the interpretation and the worldview operates in history and is seen as a ‘development’; indeed it has been so logically in history because for Western man the truth, or God Himself, has become incarnate in man in time and in history.

Of all the great religions of the world Christianity alone shifted its center of origin from Jerusalem to Rome, symbolizing the beginnings of the westernization of Christianity and its gradual and successive permeation of Western elements that in subsequent periods of its history produced and accelerated the momentum of secularization. There were, and still are from the Muslim point of view, two Christianities: the original and true one, and the Western version of it. Original and true Christianity conformed with Islam. Those who before the advent of Islam believed in the original and true teachings of Jesus (on whom be Peace!) were true believers (mu’min and muslim). After the advent of Islam they would, if they had known the fact of Islam and if their belief (imān) and submission (islām) were truly sincere, have joined the ranks of Islam. Those who from the very beginning had altered the original and departed from the true teaching of Jesus (Peace be upon him!) were the creative initiators of Western Christianity, the Christianity now known to us. Since their holy scripture, the Gospel, is derived partly from the original and true revelation of Jesus (upon whom be Peace!), the Holy Qur’ān categorizes them as belonging to the People of the Book (Ahl al-Kitāb). Among the People of the Book, and with reference to Western Christianity, those who inwardly did not profess real belief in the doctrines of the Trinity, the Incarnation and the Redemption and other details of dogma connected with these doctrines, who privately professed belief in God alone and in the Prophet Jesus (on whom be Peace!), who set up regular prayer to God and did good works in the way they were spiritually led to do, who while in this condition of faith were truly and sincerely unaware of Islam, were those referred to in the Holy Qur’ān as nearest in love to the Believers in Islam.39 To this day Christians like these and other People of the Book like them are found among mankind; and it is to such as these that the term mu’min (believer) is also sometimes applied in the Holy Qur’ān.

Because of the confusion caused by the permeation of Western elements, the religion from the outset and as it developed resolutely resisted and diluted the original and true teachings of Christianity. Neither the Hebrews nor the original Christians understood or knew or were even conscious of the presently claimed so called ‘radicalism’ of the religion as understood in the modern sense after its development and secularization as Western Christianity, and the modern interpretation based upon reading — or rather misreading — contemporary experience and consciousness into the spirit and thought of the past is nothing but conjecture. The evidence of history shows early Christianity as consistently opposed to secularization, and this opposition, engendered by the demeaning of nature and the divesting of it of its spiritual and theological significance, continued throughout its history of the losing battle against the secularizing forces entrenched paradoxically within the very threshold of Western Christianity. The separation of Church and State, of religious and temporal powers was never the result of an attempt on the part of Christianity to bring about secularization; on the contrary, it was the result of the secular Western philosophical attitude set against what it considered as the anti-secular encroachment of the ambivalent Church based on the teachings of the eclectic religion. The separation represented for Christianity a status quo in the losing battle against secular forces; and even that status quo was gradually eroded away so that today very little ground is left for the religion to play any significant social and political role in the secular states of the Western world. Moreover the Church when it wielded power was always vigilant in acting against scientific enquiry and purely rational investigation of truth, which seen in the light of present circumstances brought about by such ‘scientific’ enquiry and ‘rational’ investigation as it developed in Western history is, however, partly now seen to be justifiable. Contrary to secularization Christianity has always preached a ‘closed’ metaphysical world view, and it did not really ‘deconsecrate’ values including idols and icons; it assimilated them into its own mould. Furthermore it involved itself consciously in sacral legitimation of political power and authority, which is anathema to the secularizing process. The westernization of Christianity, then, marked the beginning of its secularization. Secularization is the result of the misapplication of Greek philosophy in Western theology and metaphysics, which in the 17th century logically led to the scientific revolution enunciated by Descartes, who opened the doors to doubt and skepticism; and successively in the 18th and 19th centuries and in our own times, to atheism and agnosticism; to utilitarianism, dialectical materialism, evolutionism and historicism. Christianity has attempted to resist secularization but has failed, and the danger is that having failed to contain it the influential modernist theologians are now urging Christians to join it. Their fanciful claim that the historical process that made the world secular has its roots in biblical faith and is the fruit of the Gospel must be seen as an ingenious way of attempting to extricate Western Christianity from its own self-originated dilemmas. While it is no doubt ingenious it is also self-destructive, for this claim necessitates the accusation that for the past two millennia Christians including their apostles, saints, theologians, theorists and scholars had misunderstood and misinterpreted the Gospel, had made a grave fundamental mistake thereby, and had misled Christians in the course of their spiritual and intellectual history. And this is in fact what they who make the claim say. If what they say is accepted as valid, how then can they and Christians in general be certain that those early Christians and their followers throughout the centuries who misunderstood, misinterpreted, mistook and misled on such an important, crucial matter as the purportedly secular message of the Gospel and secularizing mission of the Church, did not also misunderstand, misinterpret, mistake and mislead on the paramount, vital matter of the religion and belief itself; on the doctrine of the Trinity; on the doctrine of the Incarnation; on the doctrine of the Redemption and on the reporting and formulation and conceptualization of the revelation? Since it ought to be a matter of greater importance for them to believe that the report of the very early Christians about the nature of the God Who revealed Himself to them was true, it would be for them to overcome this problem by resorting to belief in human ‘evolution’ and historicity and the relativity of truths according to the experience and consciousness of each stage of human ‘evolution’ and history, for we cannot accept an answer based merely on subjective experience and consciousness and ‘scientific’ conjecture where no criteria for knowledge and certainty exist. What they say amounts to meaning that God sent His revelation or revealed Himself to man when man was in his ‘infantile’ stage of ‘evolution’. ‘Infantile’ man then interpreted the revelation and conceptualized it in dogmatic and doctrinal forms expressing his faith in them. Then when man ‘matures’ he finds the dogmatic and doctrinal conceptualizations of ‘infantile’ man no longer adequate for him to express his faith in his time, and so he must develop them as he develops, otherwise they become inadequate. Thus they maintain that the dogmatic and doctrinal conceptualizations ‘evolve’, but they ‘evolve’ not because they are from the very beginning necessarily inadequate, but because as man ‘develops’ they become inadequate if they fail to develop correspondingly. This in our view of course does not solve the problem of the reliability of the reporting of the revelation, the more so when it was the work of ‘infantile’ man. Moreover this way of integrating religion with the evolutionary theory of development seems to lead logically to circular reasoning. Why should God send His revelation or reveal Himself to ‘infantile’ man and not to ‘mature’ man, especially since God, Who created man, must know the stage of growth at which he was at the moment of the revelation? Even a man would not send a vitally important message or reveal himself meaningfully to an infant. They may answer that God did not send His revelation or reveal Himself to ‘mature’ man but to ‘infantile’ man instead precisely in order to initiate the process of ‘maturing’ in him so that when he ‘developed’ to ‘maturity’ he would be able to know its meaning and purpose. But then, even in his allegedly ‘mature’ stage in this modern, secular age, Western man is still inadequately informed about God, and still groping for a meaning in God. It seems then that Western man who believes in this version of Christianity must either admit that man is still ‘infantile’, or that the revelation or the conceptualization of its meaning and purpose is from the very beginning necessarily inadequate. As regards the revelation itself, it would be impossible for them to ascertain beyond doubt that it was reliably formulated and reported, for there exists other reports, apart from that of St. Barnabas, and both from the Ante-Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, which contradicted the report on which the conceptualization which became the ‘official’ version of Christianity now known to us is based.

Western man is always inclined to regard his culture and civilization as man’s cultural vanguard; and his own experience and consciousness as those representative of the most ‘evolved’ of the species, so that we are all in the process of lagging behind them, as it were, and will come to realize the same experience and consciousness in due course sometime. It is with this attitude that they, believing in their own absurd theories of human evolution, view human history and development and religion and religious experience and consciousness. We reject the validity of the truth of their assertion, with regard to secularization and their experience and consciousness and belief, to speak on our behalf. The secularization that describes its true nature clearly when applied to describe Western man and his culture and civilization cannot be accepted as true if it is intended to be a description of what is happening in and to the world and man in which it is also meant to be applicable to the religion of Islam and the Muslims, and even perhaps to the other Eastern religions and their respective adherents. Islam totally rejects any application to itself of the concepts secular, or secularization, or secularism as they do not belong and are alien to it in every respect; and they belong and are natural only to the intellectual history of Western-Christian religious experience and consciousness. We do not, unlike Western Christianity, lean heavily for theological and metaphysical support on the theories of secular philosophers, metaphysicians, scientists, paleontologists, anthropologists, sociologists, psychoanalysts, mathematicians, linguists and other such scholars, most of whom, if not all, did not even practise the religious life, who knew not nor believed in religion without doubt and vacillation; who were skeptics, agnostics, atheists, and doubters all. In the case of religion we say that in order to know it man’s self itself becomes the ‘empirical’ subject of his own ‘empiricism’, so that his study and scrutiny of himself is as a science used upon research, investigation and observation of the self by itself in the course of its faith and sincere subjugation to Revealed Law. Knowledge about religion and religious experience is therefore not merely obtained by purely rational speculation and reflection alone. Metaphysics as we understand it is a science of Being involving not only contemplation and intellectual reflection, but is based on knowledge gained through practical devotion to that Being Whom we contemplate and sincerely serve in true submission according to a clearly defined system of Revealed Law. Our objection that their authorities, on whose thoughts are based the formulation and interpretation of the facts of human life and existence, are not reliable and acceptable insofar as religion is concerned on the ground stated above is valid enough already. We single out religion because we cannot discuss the issue of secularization without first coming to grips, as it were, with religion by virtue of the fact that religion is the fundamental element in human life and existence against which secularization is working. Now in their case it seems that they have found it difficult to define religion, except in terms of historicity and faith vaguely expressed, and have accepted instead the definition of their secular authorities who when they speak of religion refer to it as part of culture, of tradition; as a system of beliefs and practices and attitudes and values and aspirations that are created out of history and the confrontation of man and nature, and that ‘evolve’ in history and undergo a process of ‘development’, just as man himself ‘evolves’ and undergoes a process of ‘development’. In this way secularization as they have defined it will of course be viewed by the theists among them as a critical problem for religion precisely because man believes that his belief cast in a particular form — which according to the atheists is an illusion — is real and permanent; whereas in point of fact — at least according to the modern theists — it must change and ‘develop’ as man and history ‘develop’. Now when the religion undergoes ‘development’ in line with human ‘evolution’ and historicity and is indeed true in their case, just as secularization is true and seen as a historical development in their experience and consciousness.40 We say this because, from the point of view of Islam, although Western Christianity is based on revelation, it is not a revealed religion in the sense that Islam is. According to Islam the paramount, vital doctrine of Western Christianity such as the Trinity, the Incarnation and the Redemption and other details of dogma connected with them are all cultural creations which are categorically denied by the Holy Qur’an as divinely inspired. Not only the Holy Qur’an, but sources arising within early Christianity itself, as we have just pointed out, denied their divinely inspired origin in such wise that these denials, historically valid as succinct evidence, present weighty grounds for doubting the reliability and authenticity of the reporting and subsequent interpretation and conceptualization of the revelation. The Holy Qur’an indeed confirms that God sent Jesus (Peace be upon him!) a revelation in the form known as Injīl (the Evangel), but at the same time denies the authenticity of the revelation as transmitted by the followers of some of the disciples. In the Holy Qur’an Jesus (on whom be Peace!) was sent as a messenger to the Children of Israel charged with the mission of correcting their deviation from their covenant with God and of confirming that covenant with a second covenant; of conveying Glad Tidings (Gospel) of the approaching advent of the Universal Religion (Islam) which would be established by the Great Teacher whose name he gave as Ahmad (Muhammad). The second covenant was meant to be valid until the advent of Islam when the Final and Complete Revelation would abrogate previous revelations and be established among mankind.41 So in the Holy Qur’ān God did not charge Jesus (on whom be Peace!) with the mission of establishing a new religion called Christianity. It was some other disciples and the apostles including chiefly Paul who departed from the original revelation and true teachings based on it, and who began preaching a new religion and set about establishing the foundations for a new religion which later came to be called Christianity. At the beginning even the name ‘Christian’ was not known to it, and it developed itself historically until its particular traits and characteristics and attributes took form and became fixed and clarified and refined and recognizable as the religion of a culture and civilization known to the world as Christianity. The fact that Christianity also had no Revealed Law (sharī‘ah) expressed in the teachings, sayings and model actions (i.e., sunnah) of Jesus (on whom be Peace!) is itself a most significant indication that Christianity began as a new religion not intended as such by its presumed founder, nor authorized as such by the God Who sent him. Hence Christianity, by virtue of its being created by man, gradually developed its system of rituals by assimilation from other cultures and traditions as well as originating its own fabrications; and through successive stages clarified its creeds such as those at Nicea, Constantinople and Chalcedon. Since it had no Revealed Law it had to assimilate Roman laws; and since it had no coherent world view projected by revelation, it had to borrow from Graeco-Roman thought and later to construct out of it an elaborate theology and metaphysics. Gradually it created its own specifically Christian cosmology, and its arts and sciences developed within the vision of a distinctly Christian universe and world view.

From its earliest history Western Christianity, as we have pointed out, came under the sway of Roman influences with the concomitant latinization of its intellectual and theological symbols and concepts which were infused with Aristotelian philosophy and worldview and were other Western elements that gradually ‘disenchanted’ nature and deprived it of spiritual significance. This divesting and demeaning of nature to a mere ‘thing’ of no sacred meaning was indeed the fundamental element that started the process of secularization in Western Christianity and the Western world. Christianity failed to contain and Christianize these elements, and unwittingly, then helplessly, allowed the secularizing developments engendered by alien forces within its very bosom to proceed relentlessly and inexorably along logical lines in philosophy, theology, metaphysics and science until its full critical impact was realized almost too late in modern times.